(This short article relies on a post in Italian that I wrote with Renato Loiero on April 29th, 2020.)

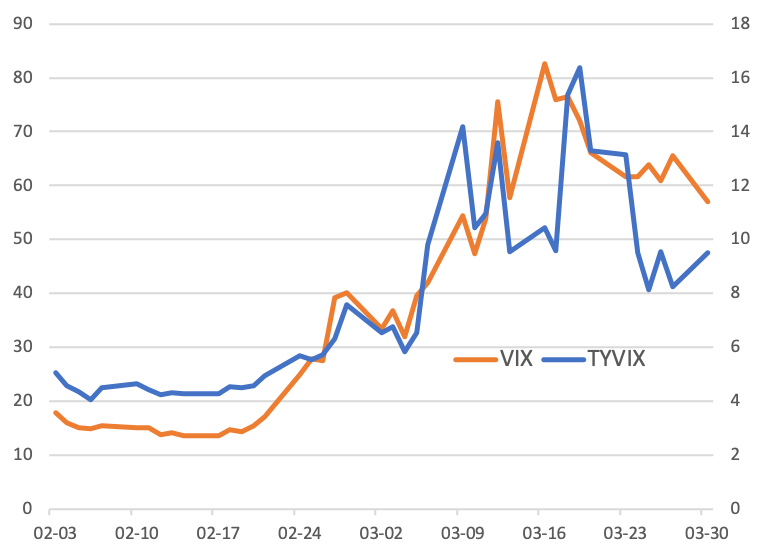

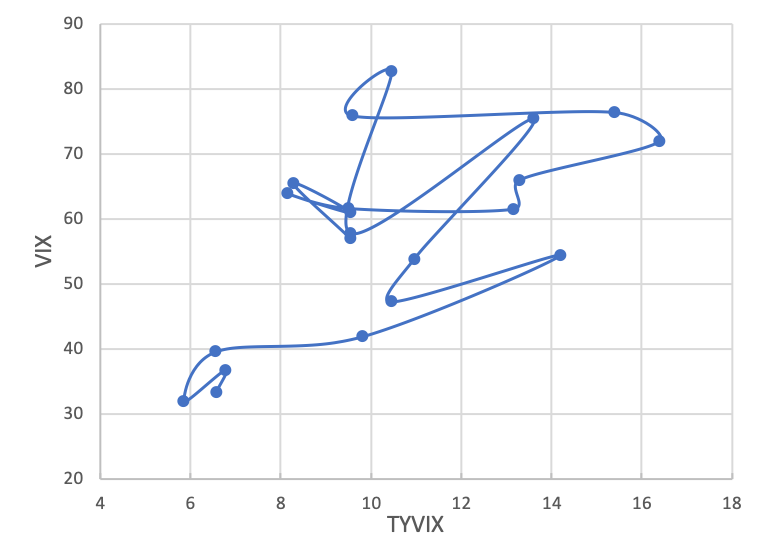

Market volatility has never been as high as during the outbreak of Covid-19. On March 16th, the VIX index maintained by maintained by Chicago Board Options Exchange (also known as the “fear index”) hit its record high of more than 82 percentage points. Market data such as future prices on VIX showed that the investors’ concerns about the economic effects of coronavirus were more acute and likely to persist more than during the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis.

The reasons underlying these developments are very clear. At the time, market evaluations were probably already very high. For example, the market was already complacent about the fact that the Federal Reserve would continue to pursue a policy with ultra-low interest rates. At the time, the only thing that would make you change your mind about market evaluations might have been the occurrence of a “Black Swan” event. Covid-19 was such an event. Its devastating effects on the economy were very clear since the beginning, with job losses reaching levels not seen since the Great Depression of the Thirties of the last century.

Market turmoil is always very worrying. When market volatility is high, investors sell. But when investors sell, market volatility raises further. This feedback loop certainly contributed to the complicated market dynamics that you observed in March and that I commented in a previous post. If, during these developments, some important financial institutions had to incur into a big loss, you would have witnessed to market dysfunctionalities reminiscent of the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis (notably, a credit crunch), with adverse consequences on an already seriously compromised real economy.

It is very reinsuring that, today, market volatility is much, much lower. At least, so it seems today, such additional spillovers will not happen. Uncertainty in financial markets and economic activity is much lower than two months ago.

Why? Economic policy around the world has certainly contributed to mitigate this uncertainty. Policy makers seem to have learnt the lessons from the Global Financial Crisis and the European Debt Crisis, injecting thousands of billion dollars into the economy throughout dedicated policy plans. Some of these plans were truly unprecedented. Certainly, humanity had to face several extremely challenging moments in the last ten or fifteen years: the Global Financial Crisis, the European Debt Crisis, migration problems, climate change problems, and, now, pandemic problems.

It is likely that, today, we will learn from these History lessons and react to the current developments with coherent policy plans. The fact that Europe is trying to come up with a common policy throughout a variety of projects shouldn’t be surprising. If Europe is a political project, it is very normal that its resolutions would reflect complex mediation mechanisms.

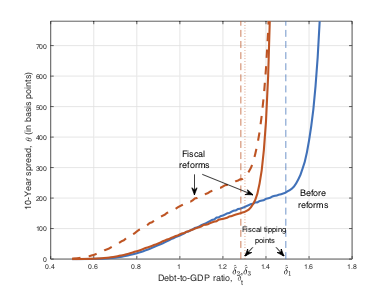

We should conclude and try to think positively. However, we need to think about the economic problems that we are about to experience soon. Covid-19 would leave humanity with a big debt burden. We shouldn’t worry too much about countries where public debt was relatively low before this crisis, such as Switzerland. We shouldn’t worry about other countries such as the United States. However, we would have to worry about some European countries, where public debt was already very high before the pandemic. This debt will have to be borne by the future generations: the more an economic system is oppressed with debt, the higher the efforts needed to be at the same level as countries with lower debt. From now on, economic development and re-construction will have to go hand in hand with financial stability. Therefore, let’s raise debt now (we have no choice), but let’s be prepared to manage its implications in the medium and long term.

This section contains a number of short writings on finance and economics and the interlinks with real developments. Some of these writings focus on brief summaries of Antonio’s recent academic research. Others suggest how this research may be interpreted in light of real market developments, past or current. This section also aims at hosting content that may hopefully stimulate academic research as well as broad debates on the role of finance and economics in our societies. The content herein should not be construed as providing the reader with any of Antonio Mele’s political views, professional advice or trading recommendations.

This section contains a number of short writings on finance and economics and the interlinks with real developments. Some of these writings focus on brief summaries of Antonio’s recent academic research. Others suggest how this research may be interpreted in light of real market developments, past or current. This section also aims at hosting content that may hopefully stimulate academic research as well as broad debates on the role of finance and economics in our societies. The content herein should not be construed as providing the reader with any of Antonio Mele’s political views, professional advice or trading recommendations. This section contains a number of short writings on finance and economics and the interlinks with real developments. Some of these writings focus on brief summaries of Antonio’s recent academic research. Others suggest how this research may be interpreted in light of real market developments, past or current. This section also aims at hosting content that may hopefully stimulate academic research as well as broad debates on the role of finance and economics in our societies. The content herein should not be construed as providing the reader with any of Antonio Mele’s political views, professional advice or trading recommendations.

This section contains a number of short writings on finance and economics and the interlinks with real developments. Some of these writings focus on brief summaries of Antonio’s recent academic research. Others suggest how this research may be interpreted in light of real market developments, past or current. This section also aims at hosting content that may hopefully stimulate academic research as well as broad debates on the role of finance and economics in our societies. The content herein should not be construed as providing the reader with any of Antonio Mele’s political views, professional advice or trading recommendations.